By Carly Elder (guest blogger)

On July 5th 2011, Kelly Thomas, a mentally ill homeless man, was beaten by police officers in a Fullerton parking lot. Five days later Thomas passed away. The beating was captured on camera and the incident sparked a national debate about the use of force by police and the treatment of those suffering from mental disorders. All six officers involved in the beating were placed on administrative leave, and two officers were charged and later acquitted of felonies leading to Thomas’ death. This case helped highlight the stigma surrounding schizophrenia as well as the fear caused by this lack of understanding.

Schizophrenia is a complex mental disorder that often involves a person “losing touch†with reality in the form of hallucinations (sensing something that others cannot see, hear, or feel), delusional thoughts, and problems with movement. This disorder is often accompanied by symptoms that mirror depression; an individual suffering from schizophrenia may have trouble focusing, problems with processing information and making decisions, as well as a poor memory. Not much is known about the neuropathology of schizophrenia, but researchers believe that there is a genetic component involved in the disorder. About one percent of the general population suffers from the disease. However, a person is ten times more likely to have schizophrenia when a first degree relative suffers from the disorder. Twin studies also support the theory that specific genes are associated with a higher risk of schizophrenia since the identical twin of someone with schizophrenia has a 40-60% chance of also having the disease.

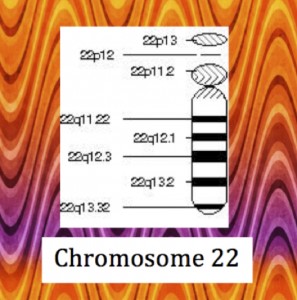

It is clear that schizophrenia is caused by defects in multiple genes as well as environmental triggers. Although a single genetic mutation will not explain schizophrenia, scientists are still looking for a correlation between the disease and certain genes. Understanding the etiology and pathology of a disease can help in designing treatments tailored to the specific condition. 22q11.2 deletion syndrome is a deletion on the long arm of chromosome 22 that is associated with schizophrenia. In a recent study, Gothelf et al. determined that a quarter to a third of people with 22q11.2 deletion syndrome have schizophrenia, and 0.3-2% of schizophrenics have this mutation. The q11.2 region of chromosome 22 codes for catechol-O-methyl transferase (COMT), an enzyme that breaks down hormones such as epinephrine, norepinephrine, and dopamine. The deletion of this gene lowers COMT production, which is associated with some cases of schizophrenia. Researchers compared individuals with this mutation to unaffected adults by measuring levels of COMT mRNA, protein levels, and enzyme activity. All of these indicators reflect how well COMT is functioning. These comparisons showed that schizophrenic individuals that had one copy of chromosome 22 with the deletion and one normal chromosome 22 produced about half as much mRNA coding for COMT, around half as much protein, and broke down target hormones at a 43% slower rate than unaffected individuals. This means that individuals with 22q11.2 deletion syndrome have higher levels of neurotransmitters in the prefrontal cortex, which is part of the brain active in regulating personality, planning, and emotion and may explain the behavior disturbances in schizophrenics.

As the scientific community continues to discover more about the role genetics plays in schizophrenia, hopefully the stigma and mystery surrounding the disorder will subside. Additionally, our growing understanding of the genetics of mental illness opens the door to predictive genetic testing (i.e. will I get schizophrenia in the future?). However, this possibility raises many ethical questions including whether or not a test that can only report a minimal increased risk for mental illness causes more harm than good if the individual tested experiences increased anxiety and worry over the result. For now, individuals who are affected by 22q11.2 deletion syndrome can be treated with drugs, therapy, and other coping methods, but further research will hopefully lead to more effective treatments.

REFERENCES

Board, A.D.A.M. Editorial. Schizophrenia. U.S. National Library of Medicine, 31 Jan. 2013. Web. 01 Mar. 2014.

“Chromosome 22.†Genetics Home Reference. U.S. National Library of Medicine, n.d. Web. 02 Mar. 2014.

“COMT.†– Catechol-O-methyltransferase. U.S. National Library of Medicine, 2007. Web. 01 Mar. 2014.

D. Gothelf, A.J. Law, A. Frisch, J. Chen, O. Zarchi, E. Michaelovsky et al. Biological effects of COMT haplotypes and psychosis risk in 22q11.2 deletion syndrome Biol Psychiatry, 75 (2014), pp. 406–413

Karas, D. J., Costain, G., Chow, E. W. C. and Bassett, A. S. (2014), Perceived burden and neuropsychiatric morbidities in adults with 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 58: 198–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2012.01639.x

“Schizophrenia.†Schizophrenia. National Institute of Mental Health, n.d. Web. 02 Mar. 2014.